Using popular science talks to foster interest in Economics among high school students

El empleo de charlas de divulgación científica para incrementar el interés por la Economía entre los estudiantes de secundaria

L’ús de xerrades de divulgació científica per incrementar l’interès per l’Economia entre els estudiants de secundària

Javier Sierra1  , Laura Padilla-Angulo2

, Laura Padilla-Angulo2  , María Jesús Manso Miguel3

, María Jesús Manso Miguel3  , José-Ignacio Antón1, 4, *

, José-Ignacio Antón1, 4, *

1 | Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain

2 | Universidad Loyola (Campus Sevilla), Sevilla, Spain

3 | IES Martínez Uribarri, Salamanca, Spain

4 | Instituto de Iberoamérica, Salamanca, Spain

*Corresponding author: janton@usal.es

Received: 24/04/2024 | Accepted: 07/11/2024 | Published: 28/01/2025

ABSTRACT: The declining interest in Economics majors in many countries among high school students and the lack of diversity of undergraduates in this field have recently become a source of concern for the academic community. In contrast with previous research examining interventions to increase the interest in Economics mostly involving impersonal communication, this work, using a sample of Spanish students, explores the impact of popular science talks targeted at upper-secondary education pupils. Our results suggest that this intervention involving personal interaction with students effectively draws the attention of high school learners to Economics. Although there seems to be no difference in its impact according to the students’ characteristics, the greater diversity of the pupil population in secondary education compared to higher education suggests that this intervention might enhance the diversity of the pool of young people studying Economics.

KEYWORDS: popular science; talks; diversity; Economics

RESUMEN: El descenso del interés por los estudios de grado en Economía y la falta de diversidad de su alumnado representa un motivo de preocupación entre la comunidad académica. A diferencia de investigaciones previas que tratan de fomentar la predisposición de los estudiantes hacia este tipo de estudios, basadas en comunicaciones de carácter impersonal, este estudio explora los efectos de charlas de divulgación científica sobre Economía sobre los estudiantes de secundaria empleando una muestra de alumnos españoles. Los resultados del trabajo ponen de manifiesto que este tipo de estrategia puede ser efectiva para elevar el atractivo de la materia y este tipo de estudios para los estudiantes de secundaria. Asimismo, dado que no encontramos diferencias en el impacto de la intervención asociadas a las características socio-demográficas de los estudiantes y que el alumnado de los grados universitarios en Economía es mucho menos diverso que el de los institutos, esta estrategia puede resultar en un incremento de la diversidad de los estudiantes de grado en Economía.

PALABRAS CLAVE: divulgación científica; charlas; diversidad; Economía

RESUM: El descens de l’interès pels estudis de grau en Economia i la manca de diversitat del seu alumnat representa un motiu de preocupació entre la comunitat acadèmica. A diferència d’investigacions prèvies que intenten fomentar la predisposició dels estudiants cap a aquest tipus d’estudis, basades en comunicacions de caràcter impersonal, aquest estudi explora els efectes de xerrades de divulgació científica sobre Economia sobre els estudiants de secundària fent servir una mostra d’alumnes espanyols . Els resultats del treball fan palès que aquest tipus d’estratègia pot ser efectiva per elevar l’atractiu de la matèria i aquest tipus d’estudis per als estudiants de secundària. Així mateix, atès que no trobem diferències en l’impacte de la intervenció associades a les característiques sociodemogràfiques dels estudiants i que l’alumnat dels graus universitaris a Economia és molt menys divers que el dels instituts, aquesta estratègia pot resultar en un increment de la diversitat dels estudiants de grau en Economia.

PARAULES CLAU: divulgació científica; xerrades; diversitat; Economia

Practitioner notes

What is already known about this topic

• There is a declining trend in the share of college students enrolled in Economics in Spain

• Women, minorities and students from low socio-economic backgrounds are underrepresented in Economics everywhere

• There is a lack of information about what Economics is about and what economists do among prospective college students

What this paper adds

• High school students in Spain greatly ignore the contents of Economics majors

• Popular science talks can raise the students’ interest in Economics by increasing the information about what Economics is and what real economists do

• This strategy can raise the representation of women, minorities and students from low socio-economic backgrounds in Economics

Implications for practice and/or policy

• Popularization talks might help students to make more informed decisions about their majors

• Information on what Economics is and what economists do might result in a composition of college students that better reflects the diversity of society, which can shape economic policies and the teaching of Economics

1. INTRODUCTION AND REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Economics is an integral part of most jobs and industries, including private businesses, non-government organisations, the administration, consulting, health, environment, and finance, informing numerous far-reaching grassroots public policies (Megalokonomou et al., 2021). Economists use data and theoretical models, for example, to evaluate public programmes, assess non-pharmaceutical interventions in a pandemic, explain social phenomena such as gender wage gaps, and examine human behaviour, such as the disclosure of certain information and its consequences for society (American Economic Association [AEA], n.d.).

However, despite its relevance, the number of Economics students has decreased in recent decades in many countries, such as the United States and Australia (Avilova & Goldin, 2018; Lovicu, 2021; Dwyer 2017; Livermore & Major 2021; Marangos et al., 2013). In Europe, according to Eurostat (2022), the proportion of students graduating in Economics has stagnated at around 1.8% between 2016 and 2019, compared to its closest alternative, namely, Business Administration (Megalokonomou et al., 2021), whose proportion of graduate students is roughly eight times higher, and has even grown in recent years, from 13% in 2016 to 17% in 2020.

In the case of Spain, graduates in Economics accounted for 2.5% of the total population completing their university studies in 2001–2002, but fewer than 1.7% in 2019–2020 (Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional & Ministerio de Universidades, 2022). This decline is even stronger among females (from 2% to 1.1%) than among males (from 3% to 2.5%).

Moreover, the gender and ethnic diversity of Economics students have traditionally been very low (Avilova & Goldin, 2018; Bayer & Rouse, 2016; Bayer &Wilcox, 2019; Dwyer 2017; Livermore & Major, 2021; Lovicu, 2021; Marangos et al., 2013; Pugatch & Schroeder, 2021a). In the US, for instance, the underrepresentation of Afro-Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans, and women in the field of Economics has been well-documented (Avilova & Goldin, 2018; Bayer & Rouse 2016; Pugatch & Schroeder, 2021a; Bayer et al., 2020b). Some studies show that underrepresented students consider this lack of diversity in Economics as a major drawback (e.g., Pugatch & Schroeder, 2021a). Recent evidence suggests that this situation also applies to the gender and socioeconomic background of PhDs (Schultz & Stansbury, 2022). For example, regarding gender, women’s representation in the economics profession at the university has stagnated worldwide since the mid-2000s, being only 35 percent of Ph.D. students and 30 percent of assistant professors (Lundberg and Stearns, 2019). Similarly, a newly released British report indicates that undergraduate students in Economics in the UK tend to come from much more privileged social backgrounds than the average pupils in higher education (Paredes Fuentes et al., 2023). For example, the proportion of them coming from families where parents attended college and have high occupational attainment and who studied at private schools or not living in areas where participation in university education is low is higher than average.

In Europe, male graduates also outnumber females in Economics. This gap has widened over the period 2013–2018, as shown by Megalokonomou et al. (2022), whereby on average only two out of every five Economic students were females. This underrepresentation might hinder the advancement in the field by limiting the array of topics addressed and constraining “our collective ability to understand familiar issues from new and innovative perspectives” (Bayer & Rouse, 2016, p. 221). This negative development over time has been even more accentuated in Spain: the percentage of females among graduates in Economics declined from nearly 51% in 2000–2001 to around 41% in 2019–2020 (Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional & Ministerio de Universidades, 2022).

Information affects the choice of studies, and the AEA, therefore, recommends sharing information to increase diversity in Economics (Bayer et al., 2019; Pugatch & Schroeder, 2021a). There is a general misconception about Economics. In particular, a common belief is “students think that economics is only for those who want to work in the financial and corporate sectors and do not realize that economics is also for those with intellectual, policy and career interests in a wide range of fields” (Avilova & Goldin, 2018, p. 186). This contrasts with the view held by most academic practitioners nowadays, who consider that Economics is an eminently empirical discipline, open to collaborative relationships with other Social and Natural Sciences that adopts scientific methods to resolve social problems (Angrist et al., 2017; Angrist et al., 2020; Bayer et al., 2020a). The information students have regarding the subject’s content and its pertinence is often insufficient (Bayer et al., 2020b; Avilova & Goldin, 2018). For example, students are unaware of the usefulness of economics in traditionally female-oriented occupations in health and development, limiting its attraction (Avilova & Goldin, 2018).

However, relatively few efforts have been made to understand why Economics is not an attractive degree and evaluate the interventions aimed at increasing its appeal (Bayer et al., 2020b; Livermore & Major, 2021), and they tend to focus on the US. To fill this gap in the literature, we explore the potential of popular science talks on Economics as an eminently empirical Social Science that seeks to address relevant topics using quantitative tools as close as possible to the scientific method to raise secondary-school students’ interest in Economics in Spain. We find that roughly two out of three pupils reported that their interest in the discipline increased with the talk. We do not detect any differences by gender, parental education, migrant background, or preconceptions about the object of study. Given that diversity is often lower in higher education than at secondary school (as in Spain), this finding suggests that this type of intervention might increase the diversity of the student pool in Economics.

This article aims to contribute to the literature in several ways: first, by examining an intervention involving personal interaction with students, whereas the majority of previous research tends to focus on impersonal communication (Pugatch & Schroeder, 2021a); second, by focusing on high-school students, as previous literature tends to focus on first-year college students; third, by exploring the effect of preconceptions about Economics on the impact of informative interventions; finally, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine a sample of students from an EU country. This aspect could be relevant given that, in contrast to the US, young Europeans have to choose a university degree before they enrol in higher education.

The rest of the paper is organised into four further sections as follows: section two reviews the recent literature on the topic; the third one describes the data collection process and outlines the main features of the intervention and methodology employed for assessing the impact of the talks; the fourth section discusses our main results, and the final one summarises the study’s main conclusions and implications and proposes future pathways for research.

2. INCREASING DIVERSITY IN ECONOMICS AND RESEARCH HYPOTHESIS

2.1. The relevance of diversity in Economics

The lack of diversity among Economics students has been widely documented (Avilova & Goldin, 2018; Bayer & Rouse, 2016; Bayer & Wilcox, 2019; Castellanos Rodríguez, 2021; Livermore & Major, 2021; Lovicu, 2021; Megalokonomou et al., 2022). The resulting shortcoming in the Economics profession compromises the field by limiting the issues examined by economists and related policy recommendations due to the dearth of viewpoints and perspectives in different sectors (May et al., 2014; Pugatch & Schroeder, 2021a; Bayer et al., 2020a). For example, in academics, Lundberg and Stearns (2019) find that female Ph.D. recipients are more likely than men to do research on labor and public economics and less likely to do research in macroeconomics and finance than men, and in general are more interested than men in applied economics, and May et al. (2014) find that female economists tend to support more government intervention than market solutions than male economists.

Economists can influence public policy that affects many different groups of people, and it is easier to take into account the effects of those policies on all those different types of people of people if they are reflected in those economists influencing policies (Mester, 2021). Relatedly, diversity in Economics, as in any other field, means variety in points of view and tends to result in better information processing since, as Mester posited in her speech at the American Economic Association Paper Session - Allied Social Science Associations Annual Meeting “they are forced to confront a different way of thinking and to convince those with alternative views”. This lack of diversity in the Economics profession also means a scarcity of role models for typically underrepresented groups in the field, such as for Black, Latinx, and Native Americans in the US, as documented in Bayer et al. (2020b). Importantly, this lack of role models is considered one of the most important barriers to the progress of minorities in an economics career (Bayer et al., 2020b).

2.2. Information provision and lack of diversity in Economics

Some studies contend that one of the main reasons for this reduced diversity and diminished appeal for Economics is the lack of accurate information regarding the content and pertinence of Economics for a variety of sectors, often not perceived as related to the field, such as health, education, inequality, development, and other social problems (Avilova & Goldin, 2018; Bayer et al., 2020a; Lovicu, 2021). In effect, previous research, such as that by Bayer et al. (2020b) finds that for many undergraduate students, it is not clear where one can work and what one can do with a degree in economics. In particular, students typically think that the clearest career path is working in a bank, and do not have enough information regarding the connection between economics and public policy both in public and private institutions (Bayer et al., 2020b). Students tend to better understand the career path after a business degree than after an economics degree (Bayer et al., 2020b). This lack of information is particularly relevant among groups that tend to be underrepresented in Economics. As one of the students interviewed for the research by Bayer et al., 2020b posits: “I know that as a minority, many of us did not grow up in an environment where business or careers are necessarily discussed. My parents were blue collar workers. College was a complete unknown other than a degree will help you” (p. 201).

Providing accurate information about the true wealth of Economics, as Bayer et al. (2019) posit, “can draw students with diverse goals, perspectives, and backgrounds into economics classrooms and into the field” (p. 110). For example, family and friends tend to highlight the relevance of Economics for employment in finance and banking, disproportionately promoting the major in Economics among males (Avilova & Goldin, 2018). Emphasising the behavioural dimension of Economics might attract more women, given the popularity among females of studies such as psychology (Mester, 2021).

2.3. Interventions providing information on Economics

Acknowledging this generalised lack of information, some researchers have designed interventions precisely to overcome this lack by providing information on different dimensions of Economics (e.g., research topics, career paths open to economists, and attractive salaries), and some works assess the effectiveness of those interventions at increasing students interest on Economics and in turn diversity. For example, Bayer et al. (2019) designed a randomised controlled trial (RCT) with 2,710 students from nine US colleges to evaluate whether sending two types of nudge emails (by faculty members) with information about Economics to incoming university students affected the number of Economics courses they ended up taking. One email consisted of a welcome message encouraging students to consider enrolling in Economics courses, and the other also contained information on the diversity of topics in Economics and the lines of research being conducted. In particular, this second email included links to educational resources on the AEA website explaining what Economics is, examples of research conducted by economists, and brief presentations by various people and positions in Economics. They found that both messages were effective, but that the second email had a bigger impact on the enrolment in Economics courses in the first semester, suggesting that who is attracted to Economics is significantly affected by the way in which Economics is presented to students.

Pugatch and Schroeder (2021) also resorted to an RCT with over 2,200 students registered in Economics Principles to assess the impact on socioeconomic and ethnic diversity among Economics undergraduates by sending nudge messages with different types of information on the subject. In particular, the first type of message encouraged students to enrol on Economics courses at a US university based on the description of the Economics major on the departmental website (basic message); the second message also included information on the remuneration of Economics graduates at different stages of their career (first year and fifteen years after graduating); the third kind of message added to the nudge message a link to an AEA video showing that Economics could be a rewarding option by talking about career opportunities, seeking to fill information gaps among underrepresented students in Economics; and the fourth type of message also added to the nudge message a link to a video introducing recent and current (diverse) Economics students and former alumni. According to this work, the messages raised the percentage of first-generation migrant or underrepresented minority students majoring in Economics. However, their messages only had an effect on male students.

Related research examines the impact of information interventions on female participation in Economics, and suggests that women require more engagement (e.g., involving personal interaction) than simple light-touch interventions such as emails (Pugatch & Schroeder, 2021b). For example, a previous article by Pugatch and Schroeder (2021b) uses the same types of treatments as in their subsequent paper (2021a), running an RCT among over 2,000 students enrolled in Economics Principles at a US university. They examined whether the students’ response to messages varies depending on gender. In the first phase, students randomly received one of the four types of messages (a control group did not receive any message). In the second phase, all the students with grades of B− or higher received a message after the course encouraging them to take the major in Economics. For a randomly chosen subset of these students, the message also encouraged them to take additional Economics courses even if their grades were not as high as they initially hoped. They found that the basic message increased the percentage of male students majoring in Economics by two percentage points, while the impact on females was null.

Li (2018) conducted an RCT with 450 students in Introductory Economics classes at a large American university. The (randomized) intervention consisted in providing information on the career prospects and potential earnings of Economics majors via a video presentation and disseminating a pamphlet and the grade distribution by sending emails to female students with a grade at or above the median, acknowledging their achievement in the course and encouraging them to consider majoring in Economics. This step, together with mentoring, increased the probability that female students with grades above the median majored in Economics.

A study by Porter and Serra (2020), based on an RCT with 627 female students, indicated that a visit by a female role model in the Economic Principles class at a US university increased the probability of female students majoring in Economics. Other RCTs, nevertheless, involving impersonal communication were unable to detect any impact among female students. These works included emails with information on relative grades in Introductory Economics (Antman et al., 2022), or emails and physical letters encouraging students to major in Economics by reassuring the students on their ability, giving information on career prospects, and non-earning and earning benefits associated with the major (Halim et al., 2022).

The RCT carried out by Bedard et al. (2021) allowed the authors to examine the effect of similar nudges toward majoring in Economics among females and under-represented minority and ethnic groups. Faculty sent personalised letters to 2,338 students receiving a minimum grade of C in the introductory principles of Microeconomics at a US university. The letters contained basic information about two Economics majors, career paths, and an invitation to a meeting providing more details about those majors. A random sample of students with a minimum grade of B in the induction course received a personalised letter acknowledging their good performance, reassuring them of their ability to complete the major in Economics, and encouraging them to do so. The positive message increased the probability of attending the meeting and majoring in Economics among both males and females, and the biggest impact on majoring in Economics was among Hispanic students, especially female ones.

Based on the above literature, we hypothesise that popular science talks will increase the interest in Economics among high-school students. Regarding the heterogeneity of the impact of our intervention, previous research on this topic does not allow us to have clear expectations on which groups of students could potentially show a stronger response.

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between May 2021 and May 2022, we held four talks in two state secondary schools in Salamanca (Spain), which is the location of the university of reference for those educational centres. These institutions hosted the events (which were subject to attendance restrictions because of the COVID-19 health crisis). The talks consisted of a 60-minute lecture centred on presenting Economics as an eminently empirical Social Science that seeks to address socially relevant topics, such as employment, poverty, inequality, or environmental issues, using quantitative tools as close as possible to the scientific method. The presentation heavily drew on specific examples. In particularly, we took the findings from well-known papers, such as the recent RCT led by economists in Bangladesh to assess the effect of masks against COVID-19 (Abaluck et al., 2022), the study documenting the impressive impact (with external effects) of school-based deworming in Kenia (Miguel & Cremer, 2004), the work based on the reservation policy adopted in the Indian constitution, which exemplifies that the gender of policy makers matters (Chattopadhyay & Duflo, 2004), the pioneering paper on the toll military service takes on individuals (Angrist, 1990), the research that highlights the substantial role of pre-school programmes or the recent evidence on the non-negative consequences of the introduction of minimum wages in Germany (Dustmann et al., 2022). We also stressed the value of descriptive evidence, as the maps of social mobility produced by Chetty et al. for the US (2014). As mentioned above, most of the profession should be comfortable with this view of the discipline.

The students, aged between 15 and 18, were either in the second year of lower-secondary school (mandatory education) or in the learning itinerary of Social Sciences in the two upper-secondary years (Spanish baccalaureate). The latter cycle comprises two-semester courses in Introductory Economics and Business Economics in the first and second years, respectively. Whereas the former subject focuses on the basics of supply and demand and macroeconomic concepts, the latter deals with the internal functioning of firms together with notions of accountancy.

Overall, we collected data from 96 of those present using Socrative (2021), an online tool that allows posing several questions to the class at a pace fully controlled by the speaker, which the sample can respond to anonymously via their smartphones. This instrument is widely used in both secondary and higher education for dynamising the classroom, promoting collaborative learning, and fostering student engagement (Bello Pintado & Díaz de Cerio, 2017; Christianson, 2020; Dervan, 2014). The talks involved two key multiple-choice questions. The first one, posed before starting the talk, was “To which sorts of concepts do you associate the word Economics?”, and had two possible answers (“A. Poverty and unemployment” and “B. Financial markets and cryptocurrencies”). The second one, to be answered at the end of the activity, simply asked whether or not the students’ interest in Economics had been increased by the talk. The data-gathering process was remarkably successful, as we obtained completed registers from 92 of the participants, with four missing observations due mainly to technical problems. After the second question, and with the aim of exploring how the impact of the talk differs according to observable characteristics, we included three additional fields for retrieving self-reported information on gender, parental education (the highest schooling level achieved by either parent) and migrant background (whether either parent had been born abroad).

Since we try to put our results in context, we resort to other sources to verify whether this type of intervention can foster diversity in higher education. In this respect, we need to know the socio-demographic composition of both secondary and higher education students in Spain. We obtain such information from two sources. First, we retrieve aggregate administrative data from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Professional Training and the Spanish Ministry of Universities (Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional, 2022). Second, we exploit the micro-data of the European Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) (Eurostat, 2021). This database records the field of study of ongoing students from 2003 to 2013.

In order to determine whether the talk affected students’ views on Economics, we employ descriptive and inferential statistical methods for examining how they thought the talk had shaped their interest in Economics, and how such a pattern differs by gender, parental education, and migrant background. Furthermore, with the aim of exploring the heterogeneity treatment effect across these characteristics, we complement our quantitative analysis by estimating a probit model of the likelihood of reporting a higher interest in Economics after the talk as a function of the three latter covariates. Although Socrative allows retrieving the answers in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, 2021), we process and analyse them using Stata (Version 16.1; StataCorp, 2021).

4. ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

Our sample’s descriptive statistics—presented in Table 1—show that our students’ preconceptions mean they do not tend to associate the discipline with the study of poverty and unemployment (i.e., social problems), but instead and to a much greater extent with the study of financial markets and cryptocurrencies. It also indicates that the talk increased the interest in Economics for almost seven out of ten attending (65.6%), suggesting the activity fulfilled its purpose. Regarding observable characteristics, there is essentially no difference in the proportion of students by gender; roughly 80% of the students have a parent with intermediate or higher education, and the share of students with a migrant background is below 10%.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the sample

Variable and categories |

Proportion (standard error) |

Interest in Economics increased with the talk |

|

No |

0.344 |

|

(0.048) |

Yes |

0.656 |

|

(0.048) |

Preconception of objects of study in Economics |

|

Financial markets and cryptocurrencies |

0.677 |

|

(0.048) |

Poverty and unemployment |

0.333 |

|

(0.048) |

Gender |

|

Male |

0.333 |

|

(0.048) |

Female |

0.666 |

|

(0.048) |

Parental education |

|

Low |

0.083 |

|

(0.028) |

Medium |

0.354 |

|

(0.049) |

High |

0.552 |

|

(0.051) |

Migrant background |

|

No |

0.906 |

|

(0.030) |

Yes |

0.094 |

|

(0.030) |

|

|

No. of observations = 96 |

Source: authors’ analysis.

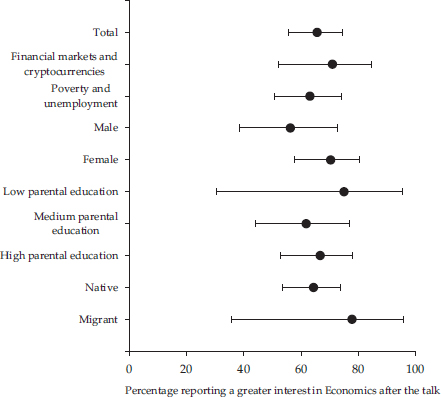

Figure 1 presents the main results of the experience. Although our sample size is somewhat limited, the proportion of those in attendance reporting a positive effect of the informative session on their interest in Economics is well above zero for all the demographic characteristics considered, confirming the potential of this type of activity involving interaction with students. The share of students reporting an increase in their interest due to the talk is particularly high for female students whose parents have little education and migrant background, and who associate Economics with financial markets and cryptocurrencies.

Figure 1. % of students reporting greater interest because of the talk, by observable characteristics

Note: The figure shows the point estimates and their 90% confidence intervals. Source: authors’ analysis.

As mentioned in Section 3, we also perform a probit analysis to determine whether the talk has a heterogeneous impact across groups, i.e., whether there are statistically significant differences in the talks’ effect according to any of the characteristics considered in the analysis. None of the four observable characteristics considered above (preconceptions about Economics, gender, parental education, and migrant background) has a significant effect on the size of the impact (Table 2). In any case, we should interpret the results shown above with certain caution because of the low number of observations.

Nevertheless, we can still draw some relevant implications from our results if we look at the composition of the student population at secondary school and higher education in Spain. Considering that the composition of the pool of secondary-school students is more diverse than that observed in undergraduate programmes in Economics, this type of action might help to increase the presence in Economics degrees of females and students from socially disadvantaged or migrant backgrounds. As mentioned above, women accounted for 40% of graduates in Economics in 2019-2020, yet for 60% of students finishing upper secondary school (Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional & Ministerio de Universidades, 2022). Unfortunately, there are no administrative data available on the characteristics of students at secondary school or in higher education (apart from gender). By pooling the 2003-2013 waves of the EU-LFS (Eurostat, 2021)—the field of ongoing education or training is regrettably not available in the survey after 2013—, we may obtain some additional insights on this issue by focusing on the population aged between 15 and 19. In particular, parental education was clearly higher among those students enrolled in social sciences, business, and law—the categories including Economics that, unfortunately, we cannot further disaggregate—than those in upper secondary school. Among the former, 39.5%, 25.5% and 35% of students had low, medium, and high parental education, respectively, whereas the percentages were 31.2%, 23.9% and 44.9%, respectively, among the latter group. Regarding migrant background, the pattern was similar: 15.5% of upper secondary-school students had at least one parent born abroad, while this figure decreased to 11.5% among college students.

Table 2. Probit analysis (average marginal effects) of the determinants of increasing the interest in Economics after the talk.

|

Average marginal effect (standard error) |

The objects of study of Economics are poverty and employment |

0.051 |

|

(0.105) |

Female |

0.087 |

|

(0.108) |

Medium parental education |

−0.083 |

|

(0.180) |

High parental education |

−0.057 |

|

(0.172) |

Migrant background |

0.161 |

|

(0125) |

|

|

Mean of dependent variable = 0.656 |

|

Correctly classified |

|

Total = 68.75% |

|

Ones = 92.06% |

|

Zeros = 24.24% |

|

Pseudo-R2 = 0.037 |

|

No. of observations = 96 |

|

Notes: *** significant at 1% level; ** significant at 5% level; * significant at 10% level. Heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors between parentheses. The model also includes an intercept and school-fixed effects. The reference category is a student whose preconception is that the objects of study of Economics are financial markets and cryptocurrencies, is male, whose parents have low education, and does not have a migrant background. Source: authors’ analysis.

As stated above, the size of our sample does not allow us to confirm the statistical significance of the differences across the various groups of students. Nevertheless, the descriptive evidence shows promising results that encourage future research using larger samples, as the proportion of students reporting an increase in their interest in Economics is particularly high among those with profiles typically underrepresented in Economics, such as females and migrants. Furthermore, the talks also foster interest in Economics among those that associate it with financial issues, as do most students in our sample.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

There exists a growing concern over the limited interest in Economics studies, particularly among females, minorities, and socially disadvantaged youngsters. As already argued, many voices consider that this lack of diversity has negative implications in many different dimensions directly affecting people’s lives. Among others, it negatively affects the diversity in the objects of study of the discipline and in the approaches regarding the evaluation of public policies. It also limits the role models that could inspire groups typically underrepresented in Economics. In this context, this research analyses the impact of popular science talks targeting upper secondary-school pupils in Spain, informing them about Economics and its aims in a comprehensive manner to overcome misperceptions. Overall, our results provide a source of optimism: this relatively low-cost intervention significantly increases the interest in Economics among high-school students with different characteristics. This effect is relatively constant across the board. Given that the diversity among high-school students is higher than among college students, this result suggests that this type of talk might become a valuable tool for increasing the diversity of undergraduates in Economics. Regarding the external validity of our study, we should mention that the socio-demographic characteristics of pupils of the public educational centers that took part in our study are quite similar to those observed in Spain as a whole. Nevertheless, we have used a relatively small sample. Moreover, we lack the necessary data to follow up with secondary-school students and link the treatment to the final choice of major.

We think that this work could be the basis for further research efforts. Particularly, the promising preliminary outcomes of this type of action make it a valuable pilot experience for a more ambitious intervention. In this respect, we believe that a school-based cluster RCT could provide much more robust and reliable evidence of this programme’s effectiveness. Specifically, future research works could explicitly explore whether it might actually help to foster enrolment in undergraduate Economics degrees. In this regard, we believe that an experimental design that randomly draws treated units from all the schools in the district willing to participate in the initiative and the employment of more concrete indicators (e.g., the percentage of applications for undergraduate degrees in Economics and related fields) might shed more light on this tool’s potential for widening the pool of students in our discipline.

Future research could also control for the performance of students in introductory Economics courses or even other subjects (e.g., Maths), as previous research finds that when deciding whether to pursue a major in Economics, female students are more sensitive to their grades in those courses when considering majoring in Economics (Li, 2018; Mester, 2021). In this fashion, one could also control for role models by asking students if they are familiar with Economics through family and friends, and also look for differences in the impact depending on their characteristics (e.g., gender and nationality).

Overall, whereas the current lack of diversity represents a source of concern, our work suggests that there might be cost-effective interventions centred on providing additional information to students that contribute to both expanding the participation of youngsters in Economics studies and achieving a more diversified socio-demographic pool than the current one. In the present international context, climate change mitigation and inequality have gained much relevance in the public debate over the last decade. Not only the Economic profession plays a quite relevant role in such a discussion, but they are also phenomena that might have very different implications on distinct socio-economic groups. These two facts call for a higher importance of diversity in the Economic discipline than ever.

6. FUNDING

We acknowledge the funding received from Unit of Scientific Culture and Innovation of the University of Salamanca (2021 Grant for Science Popularization No. 19). Laura Padilla-Angulo is grateful to the Spanish Agencia Estatal de Investigación (PDC2022-133230-I00) and Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (PID2021-126892NBI00).

7. REFERENCES

Abaluck, J., Kwong, L. H., Styczynski, A. Haque, A., Kabir, A., Bates-Jefferys, E., Crawford, E., Benjamin-Chung, J., Raihan, S., Rahman, S., Benhachmi, S., Bintee, N. Z., Winch, P. J., Hossain, M., Reza, H. M., Jaber, A. A., Momen, S. G., Rahman, A., Banti, F. L., … Mobarak, A. M. (2022). Impact of community masking on COVID-19: A cluster-randomized trial in Bangladesh. Science, 375(6577), eabi9069. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abi9069

American Economic Association (n.d.). What is Economics? Understanding the discipline. https://www.aeaweb.org/resources/students/what-is-economics

Angrist, J. D. (1990). Lifetime earnings and the Vietnam era draft lottery: evidence from Social Security administrative records. American Economic Review, 80(3), 313–336. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2006669

Angrist, J. D., Azoulay, P., Ellison, G., Hill, R., & Feng Lu, S. (2020). Inside job or deep Impact? Extramural citations and the influence of economic scholarship. Journal of Economic Literature, 58(1), 3–52. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20181508

Angrist, J. D., Azoulay, P., Ellison, G., Hill, R., & Feng Lu, S. (2017). Economic research evolves: fields and styles. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 107(5), 293–297. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20171117

Antman, F. M., Flores, N. E., & Skoy, E. (2022). Can Better Information Reduce College Gender Gaps? The Impact of Relative Grade Signals on Academic Outcomes for Students in Introductory Economics (Working Paper). Department of Economics, University of Colorado, Boulder. https://spot.colorado.edu/~antmanf/Antman-Skoy-Flores-GenderUWE.pdf

Avilova, T., & Goldin, C. (2018). What can UWE do for economics? AEA Papers & Proceedings, 108, 186–190. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20181103

Bayer, A., Bhanot, S. P., & Lozano, F. (2019). Does simple information provision lead to more diverse classrooms? Evidence from a field experiment on undergraduate Economics. AEA Papers & Proceedings, 109, 110–114. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20191097

Bayer, A., Bruich, G., Chetty, R., & Housiaux, A. (2020a). Expanding and diversifying the pool of undergraduates who study Economics: Insights from a new introductory course at Harvard. Journal of Economic Education, 51(3–4), 364–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2020.1804511

Bayer, A., Hoover, G. A., & Washington, E. (2020b). How you can work to increase the presence and improve the experience of Black, Latinx, and Native American people in the economics profession. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(3), 193–219. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.34.3.193

Bayer, A., & Rouse, C. E. (2016). Diversity in the Economics profession: A new attack on an old problem. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(4), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.4.221

Bayer, A., & Wilcox, D. W. (2019). The unequal distribution of economic education: A report on the race, ethnicity, and gender of economics majors at U.S. colleges and universities. Journal of Economic Education, 50(3), 299–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2019.1618766

Bedard, K., Dodd, J., & Lundberg, S. (2021). Can positive feedback encourage female and minority undergraduates into Economics? AEA Papers & Proceedings, 111, 128–132. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20211025

Bello Pintado, A., & Díaz de Cerio, M. (2017). Socrative: Una herramienta para dinamizar el aula [A tool to dynamize the classroom]. WPOM-Working Papers on Operations Management, 8, 72–75. https://doi.org/10.4995/wpom.v8i0.7167

Castellanos Rodríguez, L. E. (2021). Diversifying the economics profession: the long road to overcoming discrimination and sub-representation of Hispanics and African Americans. An analysis of the United States between 1995–2019. Cuadernos de Economía, 41(84), 875–897. https://doi.org/10.15446/cuad.econ.v40n84.95665

Chattopadhyay, R., & Duflo, E. (2004). Women as policy makers: evidence from a Randomized policy experiment in India. Econometrica, 72(5), 1409–1443. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0262.2004.00539.x

Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Kline, P., & Saez, E. (2014). Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(4), 1553–1623. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju022

Christianson, A. M. (2020). Using Socrative online polls for active learning in the remote classroom. Journal of Chemical Education, 97(9), 2701–2705. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00737

Dervan, P. (2014). Enhancing in-class student engagement using Socrative (an online student response system). AISHE-J: The All Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 6(3), 18001–18012. https://doi.org/10.62707/aishej.v6i3.180

Dustmann, C., Lindner, A., Schönberg, U., Umkehrer, M., & vom Berge, P. (2022). Reallocation effects of the minimum wage. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137(1), 267–328. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjab028

Dwyer, J. (2017). Studying Economics: the decline in enrolments and why it matters. Journal of the Economics and Business Educators New South Wales, 1, 11–16. https://www.ebe.nsw.edu.au/files/publications/ebe_journal/Journal_1_2017.pdf

Eurostat. (2021). European Union Labour Force Survey [Data set]. Eurostat.

Eurostat. (2022, June 10). Graduates by education level, programme orientation, sex and field of education [educ_uoe_grad02] [Database]. https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=educ_uoe_grad02&lang=en

Frisancho, V. (2020). The impact of financial education for youth. Economics of Education Review, 78, 101918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2019.101918

Halim, D., Powers, E. T., & Thornton, R. (2022). Gender differences in Economics course-taking and majoring: findings from an RCT. AEA Papers & Proceedings, 112, 597–602. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20221120

Li, H.-H. (2018). Do mentoring, information, and nudge reduce the gender gap in Economics majors? Economics of Education Review, 64, 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.04.004

Livermore, T., & Major, M. (2021). Why study (or not study) Economics? A survey of high school students (RBA Research Discussion Paper No. 2021-06). Research Bank of Australia, Canberra. https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/2021/pdf/rdp2021-06.pdf

Lovicu, G.-P. (2021). The transition from high school to university Economics. Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin, June 2021, 62–70. https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2021/jun/pdf/the-transition-from-high-school-to-university-economics.pdf

Lundberg, S., & Stearns, J. (2019). Women in economics: Stalled progress. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.1.3

Marangos, J., Fourmouzi, V. & Koukouritakis, M. (2013). Factors that determine the decline in university student enrolments in Economics in Australia: an empirical investigation. Economic Record, 89(285), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4932.12038

May, A. M., McGarvey, M. G., & Whaples, R. (2014). Are disagreements among male and female economists marginal at best? A survey of AEA members and their views on Economics and economic policy. Contemporary Economic Policy, 32(1), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12004

Megalokonomou, R., Vidal-Fernández, M., & Yengin, D. (2021, November 11). Why having more women/diverse economists benefits us all. VoxEu-CEPR Policy Portal. https://voxeu.org/article/why-having-more-womendiverse-economists-benefits-us-all

Megalokonomou, R., Vidal-Fernández, M., & Yengin, D. (2022). Underrepresentation of women in undergraduate Economics degrees in Europe: A comparison with STEM and Business. In S. Mendolia, M. O’Brien, A. R. Paloyo & A. Yerokhin (Eds.), Critical perspectives on Economics of Education (pp. 6–20). Routledge.

Mester, L. J. (2021, January 4). Remarks for the Session: “Increasing diversity in Economics: from students to professors” [Paper presentation]. Allied Social Science Associations 2021 Virtual Annual Meeting. https://www.clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/speeches/sp-20210104-remarks-for-the-session-increasing-diversity-in-economics-from-students-to-professors.aspx

Microsoft Corporation. (2021). Microsoft Excel (version 16.0) [Computer software]. Microsoft Corporation.

Miguel, E., & Kremer, M. (2004). Worms: identifying impacts on education and health in the presence of treatment externalities. Econometrica, 72(1), 179–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0262.2004.00481.x

Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional & Ministerio de Universidades. (2022). EDUCAbase [Database]. https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/servicios-al-ciudadano/estadisticas.html

Paredes Fuentes, E., Burnett, T., Cagliesi, G., Chaudhury, P., & Hawkes, D. (2023). Who studies Economics? An analysis of diversity in the UK Economics pipeline (Diversity Report: Royal Economic Society). Royal Economic Society, London. https://res.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Who-studies-economics-Diversity-Report.pdf

Porter, C., & Serra, D. (2020). Gender differences in the choice of major: the importance of female role models. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 12(3), 226–254. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20180426

Pugatch, T., & Schroeder, E. (2021a). A simple nudge increases socioeconomic diversity in undergraduate Economics (IZA Discussion Paper No. 14418). Institute of Labor Economics, Bonn. https://docs.iza.org/dp14418.pdf

Pugatch, T., & Schroeder, E. (2021b). Promoting female interest in Economics: limits to nudges. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 111, 123–127. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20211024

Schultz, R., & Stansbury, A. (2022). Socioeconomic diversity of Economics PhDs (PIIE Working Paper No. 22–4). Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington, DC. https://www.piie.com/sites/default/files/documents/wp22-4.pdf

Socrative (2021). Socrative Teacher [Computer software]. Socrative Inc. https://www.socrative.com

StataCorp (2021). Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station (Version 17) [Computer software]. StataCorp LLC.